The History of InfoAge Science & History Museums

World War II & Radar - Stealing America’s Radar SecretsStealing America’s Radar Secrets

SECRET WEAPONS

SECRET WEAPONS

of World War II

By William B. Breuer

Page 10-12The Signal Corps began its quest for radar at Fort Monmouth main post. Due to the problem below, described by William B. Breuer in his book “SECRET WEAPONS of World War II”, the development work would be moved to Fort Hancock on isolated Sandy Hook. Once the war began in Europe it became apparent that Fort Hancock was in danger of U-boat deck gun attack. The decision was made to find a safer new location for the laboratory. The search ended with the Signal Corps purchasing the old Marconi Belmar Station property from The King’s College in 1941.

Infoage would like to thank author William B. Breuer for written permission to post this story on our website.

The book was published in 2000 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-37287-0Stealing America’s Radar Secrets AT CAFE HINDENBURG in the German-American section called Yorkville in New York City, a raucous celebration was ushering in New Year 1939. As the night wore on and as copious amounts of schnapps, cognac, beer, and wine were consumed, the din grew deafening.

At one table, Karl Schlueter, a steward on the German luxury ocean liner Europa, then docked in the Hudson River, was host to a group of friends and vying for the honor of being the drunkest and the loudest. Between hefty belts of schnapps, Schlueter pawed amorously at his attractive girlfriend, twenty-seven-year-old Johanna “Jenni” Hofman, a hairdresser on the ship.

Actually, Schlueter was a spy, the Orstgruppenfuhrer (Nazi party official) who had total control of Europa under the cover of being a lowly steward. Jenni Hofman was his courier.

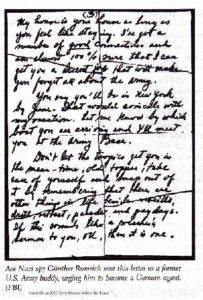

During the boisterous merrymaking at Cafe Hindenburg, Schlueter engaged in periodic conversation with a guest at his table whom he called Theo. A medium-sized man with black hair brushed straight back, Theo was the code name for Gunther Gustav Rumrich, one of the slickest and most productive Nazi spies in the United States.

Rumrich was born in Chicago, where his father, Alphonse, had been secretary of the Austro-Hungarian consulate. When Gunther was two years old, his father was transferred to a post in Bremen, Germany, and the boy grew up in a Europe ravaged by the Great War. At age eighteen he learned that because of his birth in Chicago, he was an American citizen. So on September 28, 1929, he arrived by ship in New York City to seek his fortune.

A curious mixture of shiftlessness, arrogance, cunning, and brilliance, Rumrich drifted from job to job around the country, including a hitch in the peacetime U.S. Army. Discharged from the service in 1936, he came to New York City and was recruited as an agent by the Abwehr, the German intelligence agency. Finally Rumrich had found his calling: he could live by his brains without having to exert much energy.

A curious mixture of shiftlessness, arrogance, cunning, and brilliance, Rumrich drifted from job to job around the country, including a hitch in the peacetime U.S. Army. Discharged from the service in 1936, he came to New York City and was recruited as an agent by the Abwehr, the German intelligence agency. Finally Rumrich had found his calling: he could live by his brains without having to exert much energy.

When Adolf Hitler had begun rearming Germany in the mid-1930s, he concluded that the United States, with its gigantic industrial potential, would be the “decisive factor” in any future war. So his secret intelligence service in the years ahead clandestinely established in America the most massive espionage penetration of a major power that history had known.

In the late 1930s, the United States was a spy’s paradise. No single federal agency was charged with fighting subversive activities, so spies roamed at will. Security at military installations was almost nonexistent. When one U.S. general commanding a large post in the East was asked what steps he had taken to guard against espionage, he said with a snort, “Don’t you think I’d know it if there was a Nazi spy running around here?”

Now, amid the hubbub of the New Year’s festivities at Cafe Hindenburg, Orstgruppenfuhrer Schlueter took Gunther Rumrich into a side room and handed him his new assignment: he was to obtain detailed intelligence about secret research that scientists with the Signal Corps were conducting at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. Reputedly, these experiments involved techniques for detecting aircraft at night, in fog, and through thick clouds-a process that later would be known as radar.

Neither Schlueter nor Rumrich knew that German scientists in Berlin had secretly been making great progress in developing radar, so any information on the topic extracted from the American camp would be of enormous benefit. Already the international scientific coterie had become convinced that radar would play a decisive role in any future war.

A few days later, Rumrich crossed the Hudson River and drove up to the main gate at Fort Monmouth, where supposedly top-secret experiments were being conducted. A bored sentry simply waved the Nazi spy through the entrance and went back to reading a comic book.

Rumrich, a friendly, engaging fellow, meandered around the post unchallenged, striking up conversations with army officers and scientists alike. He had no trouble locating the site of the secret experiments: he had merely asked a captain where the radar tests were taking place.

Rumrich continued his sleuthing at Fort Monmouth in the days ahead, and he was able to collect an enormous amount of intelligence on radar research and experiments. Moreover, he obtained information on other secret tests: infrared detection, and an antiaircraft detector for searchlight control and automatic gun sighting.

When Karl Schlueter returned to New York City on Europa a month later, Rumrich handed him a thick packet of scientific intelligence he had collected at Fort Monmouth. Schlueter was delighted and handed over a present from the spymasters in Germany: a one-hundred-dollar bill, more money than Rumrich had made in an entire year as a soldier in the U.S. Army.2

2. Stealing America’s Radar Secrets

Declassified FBI files, 1946, in author’s possession.

Michael Sayers and Albert E. Kahn, Sabotage! (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1942), pp. 15, 18.

Leon Turrou, The Nazi Spy Conspiracy in the United States (Freeport, N.Y.: Books for Libraries Press, 1969), pp. 58, 62

page created October 6, 2003

We Need Your Help! Volunteer with Us.

Join our mission to preserve historic Camp Evans and teach the public about science and history.

Sign up to join our team of volunteers and start on your own mission today.

InfoAge Science & History Museums

2201 Marconi Road

Wall, NJ 07719

Tel: 732-280-3000

info@infoage.org

webmaster@infoage.org